8 months ago a thread exploded on R/Dublin entitled “Do you have a "Third Place" in Dublin?”. Redditor “nithuigimaonrud hit the nail on the head with their response, “Dublin doesn’t really have public squares as we usually dedicate any village centres to car parking and put our farmers markets in industrial estates.” Ouch. But accurate.

Drury Street wasn’t designed to be a gathering place. It became one out of necessity. Pedestrianised during the pandemic, it offered something rare in Dublin: a stretch of a central street that caught the sun in the evenings. The street was full of independent locally owned businesses that people wanted to support post pandemic. Not massive chains set up in what should be state owned buildings. So young people turned it into a third place.

The youth of the city perched, passed cans, shared Aperol Spritzs, split the G, laughed, argued, flirted and made memes about it. They brought music, chatter, life. And supported man Vox Popping journalists. And the city’s response? Ire. Signs warning against loitering. Complaints about ‘anti-social behaviour’ in the national news. Public condemnation. Pearl clutching. “Won’t somebody please think of the children”. ‘The Guards are to be rang’.

Yes, some of the businesses did have legitimate cause to gripe. People littering and pissing inappropriately has always been an issue in places that have been claimed by the public as their own. While individuals are responsible for their own behaviour, this kind of thing could be avoided if the city built the amenities needed to prevent such behaviour.

Drury Street is the latest in a cycle Dublin refuses to break. We’ve seen it before. Portobello. Grand Canal Dock. Stephen’s Green. The Powerscout Steps. Organic gathering turns into perceived nuisance. Community gets rebranded as disorder. People are pushed out instead of supported. And the public spaces that could be, that should belong to the city's inhabitants are rendered inhospitable, inconvenient, or simply fenced off.

If we don’t want to keep repeating this cycle, we have to change how we think about space. We can’t keep responding to communities with conflict. We can’t keep treating impromptu public gatherings as a threat. Instead of reacting with restrictions, we need to respond with resources.

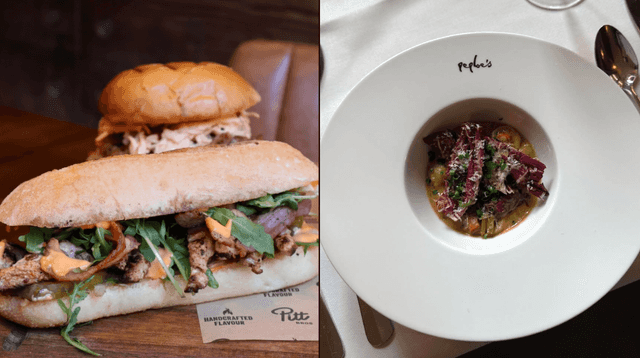

That means infrastructure: bins, benches, toilets, lighting. Shade and shelter. Places where you can be without buying. Or at least without having to buy something every hour to justify your presence. The kind of money that the average person doesn’t have any more because of the crisis trifecta. The housing crisis, cost of living crisis and the wage stagnation crisis means people have no disposable income. Therefore they have nowhere to go. We deserve spaces that don’t shut at six or require booking. Squares that belong to the people who live here. Not only to businesses, landlords, developers, and tourists. Cities like Lisbon, Copenhagen, or Ljubljana demonstrate what’s possible when public space is considered a right, not a liability.

A third place is not a radical concept. People have been talking about this for a long time. It’s not utopian. It’s a place to land when your head’s melted or you’ve been left on read again and just need to vent to a friend without dropping a fiver. It’s enough benches under trees that you aren’t elbowing people out of the way to nab one as soon as the previous occupants leave. These days we’re so starved of space we will settle for a patch of sun on a wall.

But Dublin, our so-called fair city, has made loitering a crime. The city’s message is loud and clear: keep moving, or pay up. Sit still for too long and you’ll find yourself vilified in the news. The cead mile failte is only for people who can pay. This city doesn’t feel like it belongs to the people who live here. It feels like it’s being rented out behind our backs, priced by the square foot, measured in Airbnb conversions and €5 flat whites.

It’s no coincidence. Ireland has a long, dark history with public gathering. Under British rule, Irish people were policed for assembling, for schooling, for standing still in too large a number. That fear of what people might do when they gather is still in our bones. Still in our discourse. Still in the way green space is fenced off, closed as the sun sets, the way toilets are locked after 6pm.

The absence of a place to languish le chelie isn’t neutral. It is political. To deny people the right to linger is to deny them the right to belong. And yet the city wonders why we feel alienated. Why there’s a male loneliness epidemic. Why we binge or burn out or disappear into our phones.

We need more than pop-up events designed to make us feel like it could end at any minute so we had better spend our money to keep it going. We need permanence. We need planning that values the unplanned. We have the bones. Parnell Square still waits for the cultural quarter we were promised. Smithfield has the size and the history. There are dead-end streets, disused car parks, idle overpasses. We could have skateparks, night markets, chess plazas. We could have spaces where life happens by accident.

The right to loiter is the right to exist. The right to gather is the right to imagine something better. Community doesn’t happen in boardrooms. It’s not corporate jargon thrown around by HR. It’s a real intangible thing people need to thrive. It doesn’t only exist on polling days or during election cycles. It happens on benches. On streets. On steps. It happens with small bids for connection. When someone passes you a lighter, or asks you to borrow your portable charger, or tells you about their day while you share a bag of chips.

It sounds simple but what Dublin needs is a square with benches, bins, toilets and acceptance of youth. We must demand a simple shift in values from the people we employ to guard this city. From footfall to friendship. From transactions to connection. From exclusion to welcome.

This ‘design’ problem is a political one. And political problems have political solutions. We just have to choose them. Vote for them with our time, with our money, with our feet, and with our actual votes.