The once-reliable rail line is now making people late, miserable, and poor.

For months now, regular passengers have faced delays, confusion, crowding, and rising fares. At the core of the problem is a pattern all too familiar in public transport systems: big-picture ambition undercut by everyday mismanagement.What happened in Dublin over the past six months could be poor planning or bad luck. Maybe its partly both, but it’s also textbook example of how neglect, opaque decision-making, and uneven investment unravel public systems that cities depend on.

In late August 2024, Irish Rail introduced a new timetable. On paper, it was about increasing intercity services. There was fanfare and a promise of progress. What followed was a failure in slow motion: a collapse of a timetable and of confidence in the institution. The damage was swift, visible, and is still unfolding.

For many Dubliners, taking the DART used to be a small moment of peace. You boarded the train, ideally got a window seat, and watched the Irish Sea blur by as you zipped along the bay. No traffic jams, no tolls, no steering wheel. It was routine, predictable, functional, even a bit scenic.

But it is now, for many, a daily exercise in frustration. These days trains are late, platforms are packed, and people are paying more than ever to sardine themselves in other people’s armpits. Something has shifted. This has been months of disruption, capped by a disastrous new timetable, repeated shutdowns, higher fares, and a whole lot of “we apologise for the inconvenience”.

"They sacrificed us for Belfast"

On 26 August 2024, Irish Rail restructured its timetable to prioritise an hourly Dublin–Belfast service, part of its intercity ambitions. But to accommodate this, DART and commuter lines were reshuffled, truncated, and in some cases rendered near-useless. Trains on the Northern Commuter line began terminating early at Connolly Station, forcing passengers from Louth, Meath, and North Dublin to disembark and jostle for space on already-full DART trains.

Commuters, especially those coming from Skerries or Drogheda, suddenly found themselves part of a failed experiment. Seats disappeared. Journey times lengthened. Peak-hour travel became a “dog eat dog” scramble, as one rider put it. At the time Mark Gleeson, spokesperson for Rail Users Ireland said, “We have not seen such repeated delays or such widespread passenger anger in many years”.

When service breaks down, fares go up

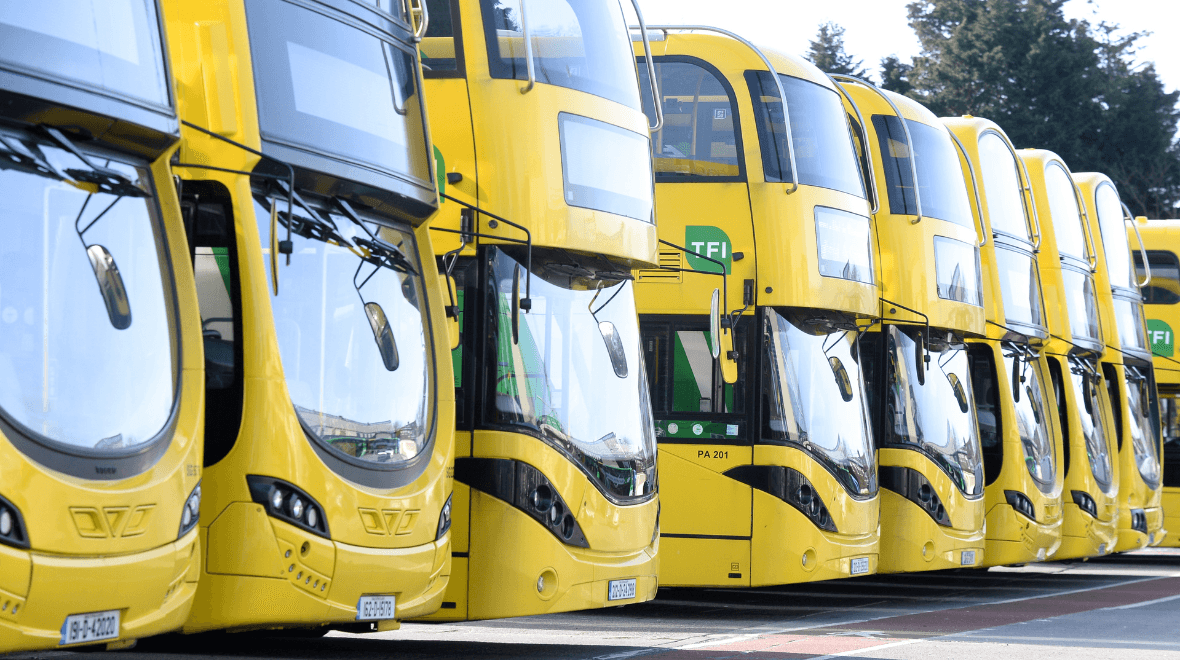

Just as service hit rock bottom, fares started climbing. Last week (April 2025), the National Transport Authority introduced a zone-based fare restructuring. This may have been justified on paper. It aligned pricing with distance. On the ground though, it felt punitive, and oddly boundaried. Some of Wicklow is still in the Dublin fare, and some is not. Parts of what is considered of North Country Dublin is zoned in with Meath.

Public outrage was both to be expected and justified. Some commuters have already started driving to Bray, to game the system. Others considered driving all the way into the city. “It’s now cheaper to drive,” one passenger told The Irish Times. Which is to say: the system designed to reduce congestion and emissions is, in practice, encouraging the opposite.

Elected officials called the fare hike “counterproductive” and “unjust.” And still, the changes went through.

Engineering works, all weekend, every weekend

This wasn’t a one-off. Irish Rail routinely uses bank holidays, Easter, May, June, October, for major works. In fact this coming May Bank Holiday Weeknd will see And while the logic might be to minimise weekday impact, the result has been to repeatedly strand leisure travellers, shift workers, and those who depend on weekend services. These planned outages, however necessary, have become a recurring disruption, with little visible return in performance or reliability.

Overcrowding and the limits of capacity

The DART is failing to meet existing demand. Carriages are crammed. Platforms are congested. The problem isn't new. Much of of Ireland's public transport has been creeping into decrepitude for many years now. But the scale of it is. Following the August timetable shake-up, many routes were shortened or consolidated, funnelling more passengers onto fewer trains. With reduced carriages and limited frequency, the system seems to have buckled.

What should be a lifeline into the city has become a daily ordeal. For many riders, there is now no guarantee of getting to work on time, or even getting on the train at all. There is anecdotal evidence in some circles that people have lost their jobs because they have been late so often to work due to these long term issues.

Communication matters

And when things go wrong, as they have been doing with stunning regularity, Irish Rail’s communication has left much to be desired. Commuters describe inconsistent announcements, missing information, and app notifications that don’t reflect reality. Trains disappear from boards. Delays go unexplained. Trains remain suspended in the no mans land between Clontarf and Connelly for swaths of time unaddressed.

This is not a minor complaint. Public transport runs on more than tracks and timetables; it runs on trust. When information is poor, people feel disrespected. When they’re told their concerns are invalid, they feel ignored. And when systems break without warning or explanation too many times, they find alternatives.

In the long term, that might mean a shift away from public transport altogether at the precise moment when Dublin can least afford it.

A public system with public consequences

The DART’s deterioration is a policy failure with real consequences. It undermines climate goals, it shifts people back to cars. It isolates communities on the edges of the network, it penalises people trying to chose rail over car, collective over individual.

And while Irish Rail has issued mea culpas, apologies alone won’t fix broken service, restore lost time, or give families the memories of the DART taking them to the Bray Jazz festival over the May Bank Holiday weekend.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is. Public transport systems around the world have faced similar moments of neglect and underinvestment. But what distinguishes those that recover is a clear understanding: transit is essential, not optional. A utility. The DART isn’t a luxury. It’s not a nice-to-have. It’s how tens of thousands of people get to work, school, and appointments. When it’s overcrowded, unreliable, overpriced, and silent it stops being a solution and becomes a problem. We need to talk about the DART to ask why the people running them keep missing the point.